The origins of Marsala

The origins of Marsala

The origins of Marsala wine

The windy coastline near the city of Marsala has welcomed merchants and adventurers from far off lands who reached this corner of Sicily by sea, since the times of the Phoenicians, who had the merit of introducing viticulture to Sicily. Strong wines with character have been produced here since ancient times, thanks to the unique residual sugars of the grapes that ripen under the scorching sun. However, it was not until 1773 that the English merchant John Woodhouse fell in love with these wines and realised their potential, so much so that he decided to send various barrels to England, but adding a good dose of brandy. This is how Marsala, as we know it today, was born.

This wine was so successful that it attracted other English entrepreneurs to Sicily, who began to produce it, and shortly afterwards the first Italian began production, namely Vincenzo Florio. Vincenzo Florio, who also arrived by sea from Calabria, devoted himself to producing this unique fortified wine, and founded the charming Wine Cellars in 1833. The history of the Florio family is full of illustrious and cultured lovers of beauty and honour, but it also reveals a history of entrepreneurial quest for modernity and innovation, which in 150 years changed the economic face of Sicily forever. The Florio Winery and Marsala wines are a vivid expression of this, and to this day continue the same avant-garde spirit looking towards the future.

The Florio winery in the 19th century

Marsala, the Sicilian wine that speaks English

Marsala has English origins: in fact, it is the result of an entrepreneurial disposition that was masterfully intertwined with the viticultural vocation of Sicily, which endowed the pragmatic British spirit with the right ‘body’ to produce a special wine, one that can conquer global markets and can be found on the most prestigious tables of the time.

The British arrived on the western coasts of Sicily mainly during the so-called ‘English decade’ (1806-1815), when King Ferdinand IV of Bourbon and his court, after fleeing from Naples and the Napoleonic troops, settled in Palermo. English merchants had been on the island for at least 30 years, mainly in Messina, Palermo, Syracuse and Marsala. John Woodhouse, who was originally from Liverpool (1730-1813), arrived here around 1773. He had come to trade barrilla (soda ash that was used to produce soap and glass) and was ‘won over’ by wine with a high alcohol content, which quickly became his most famous product.

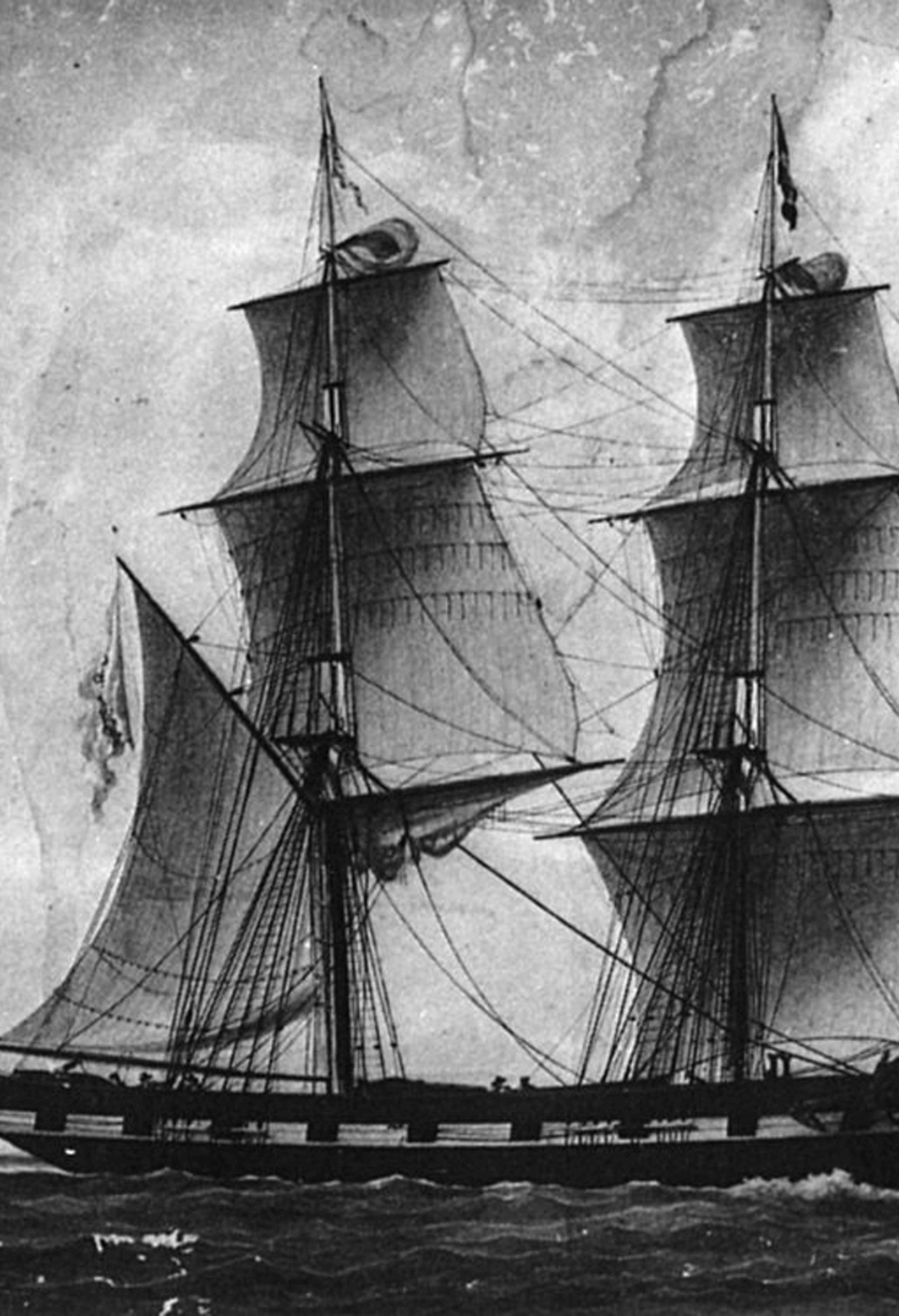

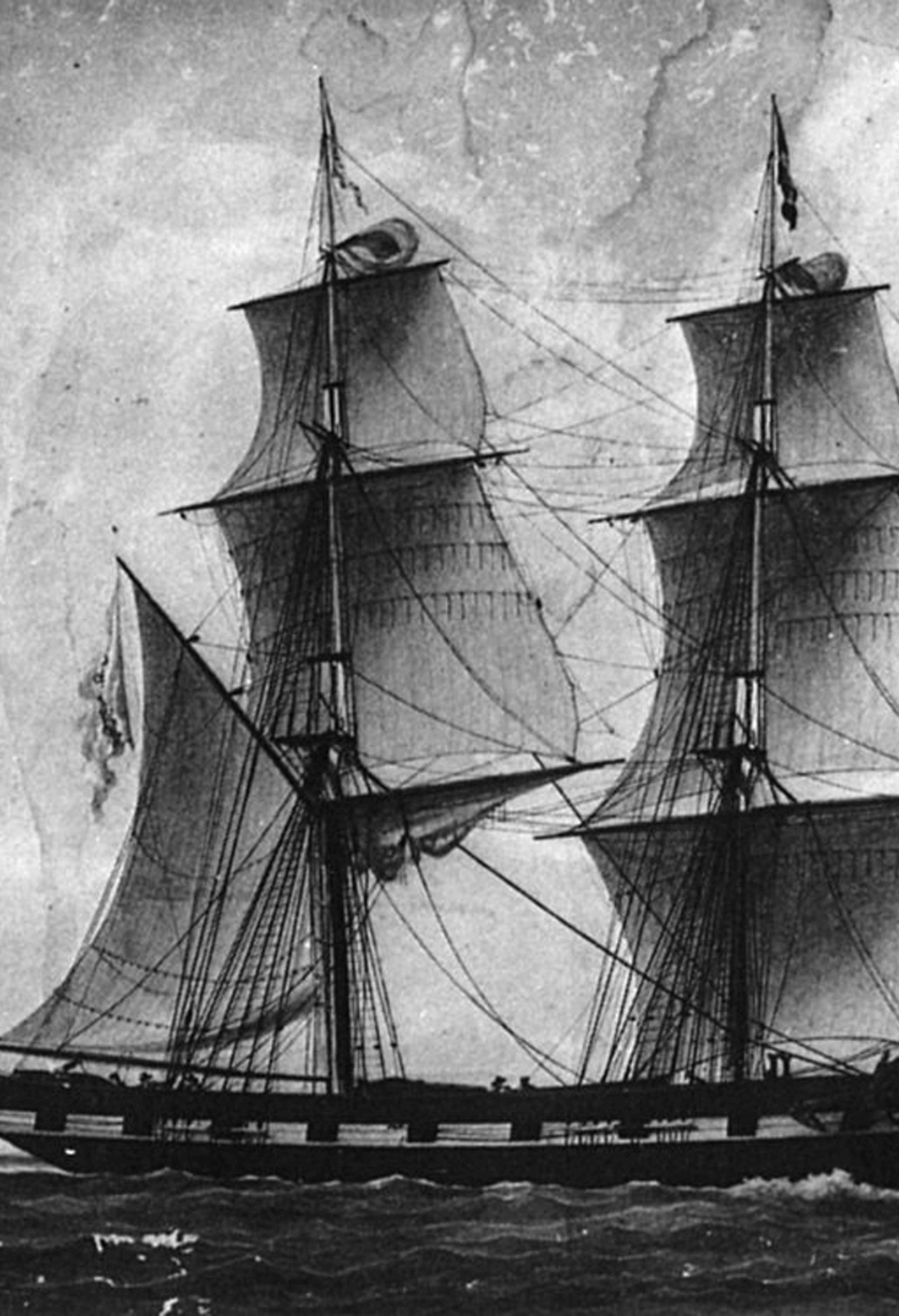

Elisabeth, John Woodhouse’s sailing ship

Marsala, the Sicilian wine that speaks English

Marsala has English origins: in fact, it is the result of an entrepreneurial disposition that was masterfully intertwined with the viticultural vocation of Sicily, which endowed the pragmatic British spirit with the right ‘body’ to produce a special wine, one that can conquer global markets and can be found on the most prestigious tables of the time.

The British arrived on the western coasts of Sicily mainly during the so-called ‘English decade’ (1806-1815), when King Ferdinand IV of Bourbon and his court, after fleeing from Naples and the Napoleonic troops, settled in Palermo. English merchants had been on the island for at least 30 years, mainly in Messina, Palermo, Syracuse and Marsala. John Woodhouse, who was originally from Liverpool (1730-1813), arrived here around 1773. He had come to trade barrilla (soda ash that was used to produce soap and glass) and was ‘won over’ by wine with a high alcohol content, which quickly became his most famous product.

Elisabeth, John Woodhouse’s sailing ship

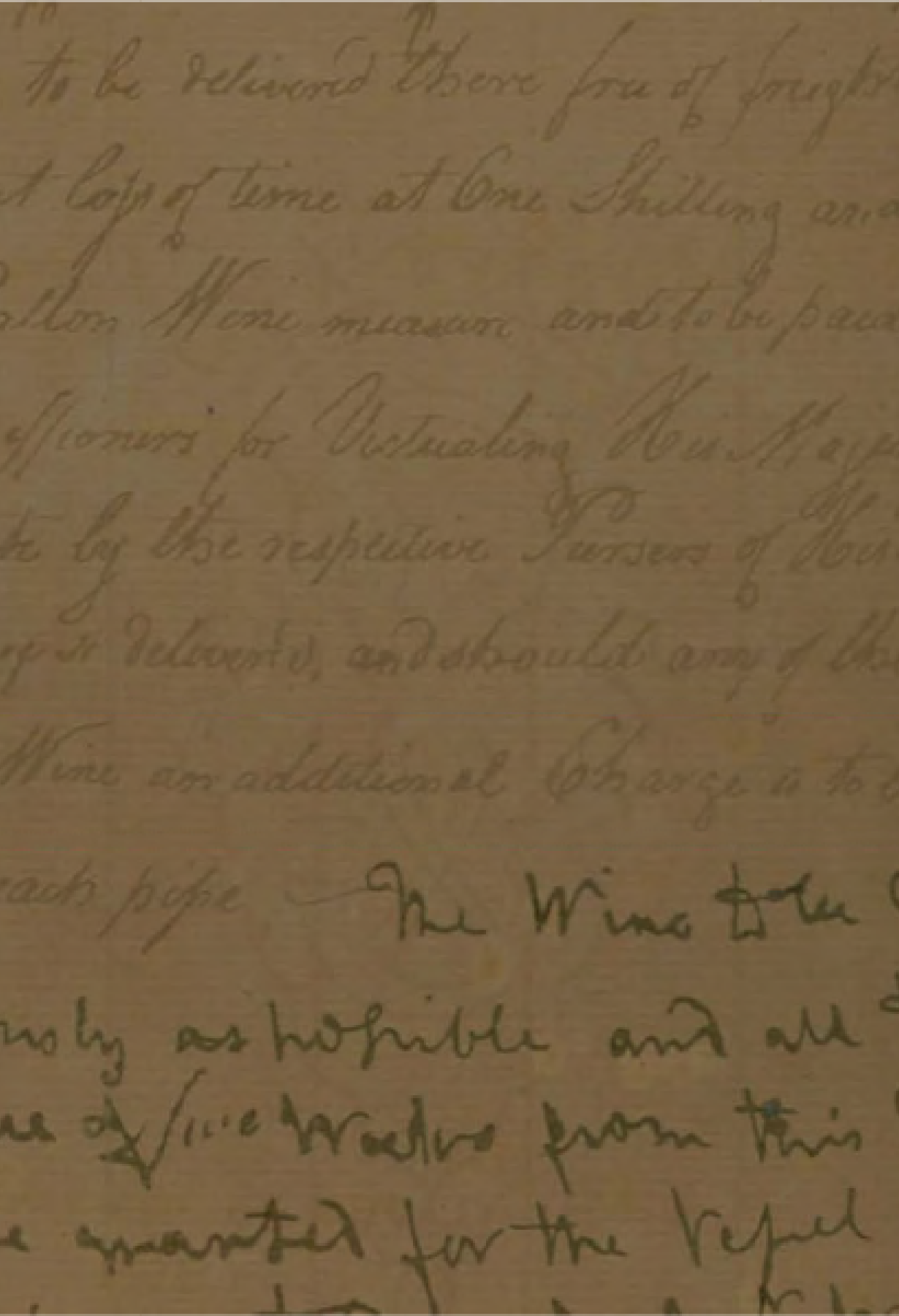

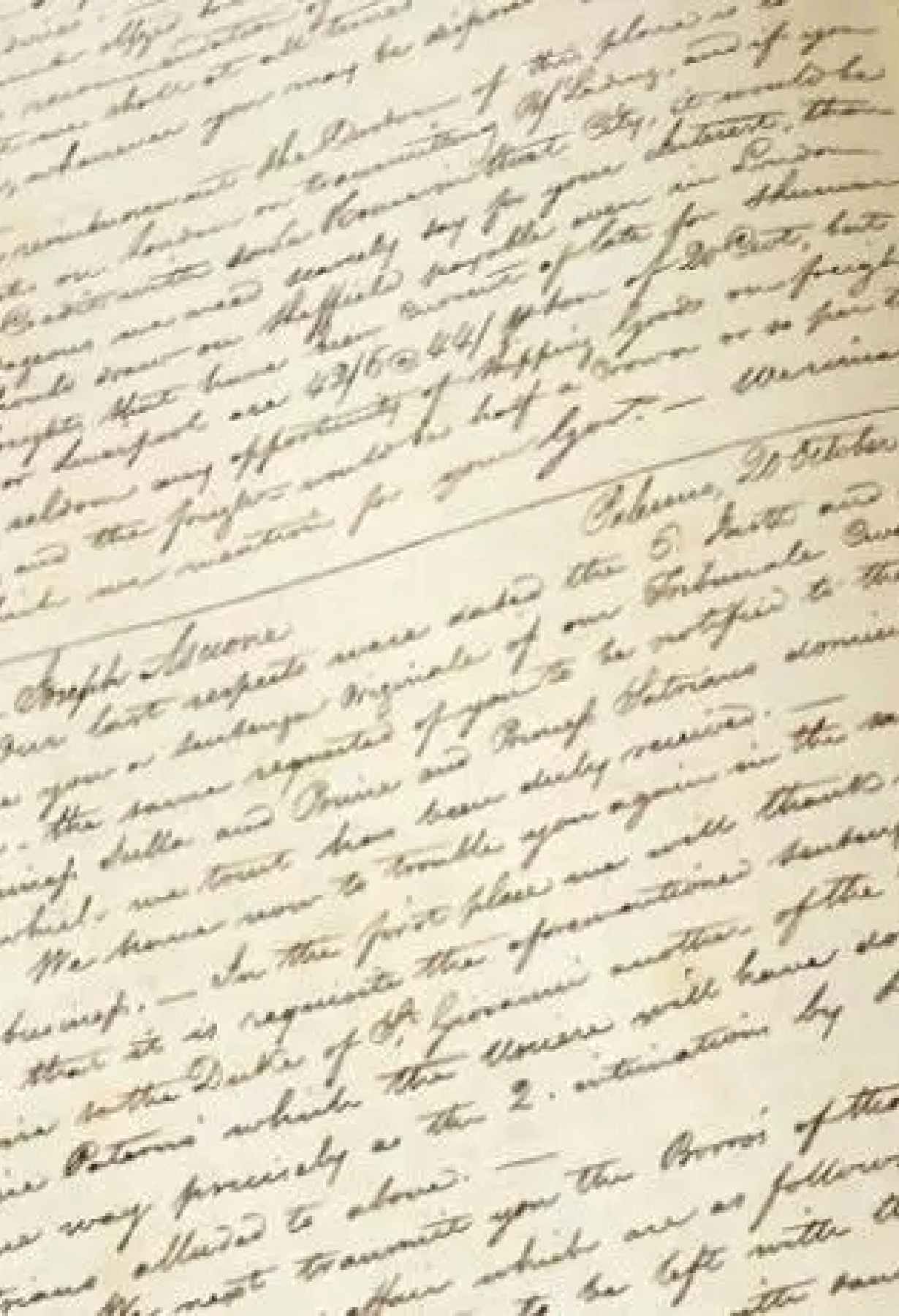

A letter from John Woodhouse on Sicilian wines

A myth to be debunked!

Why did John Woodhouse add alcohol to the shipment of Sicilian wines to be used to make Madeira wine?

The official reason is that adding distillate would have made it possible to better preserve the wine, preventing any form of secondary fermentation and stabilising the product during transhipment. However, if properly made, ‘robust Sicilian wines’ used to have significant alcohol content (even 18%) and, according to Stefano Zirilli (one of the most prominent Sicilian wine producers of the late 1800s), this was more than sufficient to ‘sail to the ends of the world’.

So, did the addition of brandy help to preserve the quality of the product during long voyages? Or was it simply the producer’s desire to apply the ‘concia’ method to Sicilian wines in order to make them more pleasing to their recipients? This is the theory put forward by Rosario Lentini, an insightful scholar of the history of Marsala. In his latest essay ‘Sicilie del vino nell’800’, Lentini proves that Woodhouse was certainly not acting randomly, let alone empirically.

ROSARIO LENTINI, Sicilie del vino nell’800, Palermo University Press, Palermo 2019, pp. 57.

‘Factory Wine’

One thing is certain: after the first successful shipment of wine, John Woodhouse and his son John Woodhouse Jr. started working on rationalising the fortification process of Marsala by establishing a ‘Wine Factory’ that had stills operating throughout the day, with specialised workers for barrel manufacturing, and a department responsible for clarifying and adding brandy to the wine. In 1804, the economist Paolo Balsamo, who had first-hand information from factory workers, wrote: ‘I was told that the famous Woodhouse wines contained no less than twenty-five per cent, namely, a quarter, of excellent brandy. In this way, the wine is able to last and withstand navigation while catering to the taste and preferences of those who purchase it.’ If this was the case, concludes Rosario Lentini, the addition of brandy was certainly a way to make the wine ‘seem more appealing to the British who preferred wines with higher alcohol content, rather than having enochemical purposes.’

ROSARIO LENTINI, Sicilie del vino nell’800, Palermo University Press, Palermo 2019, pp. 57.

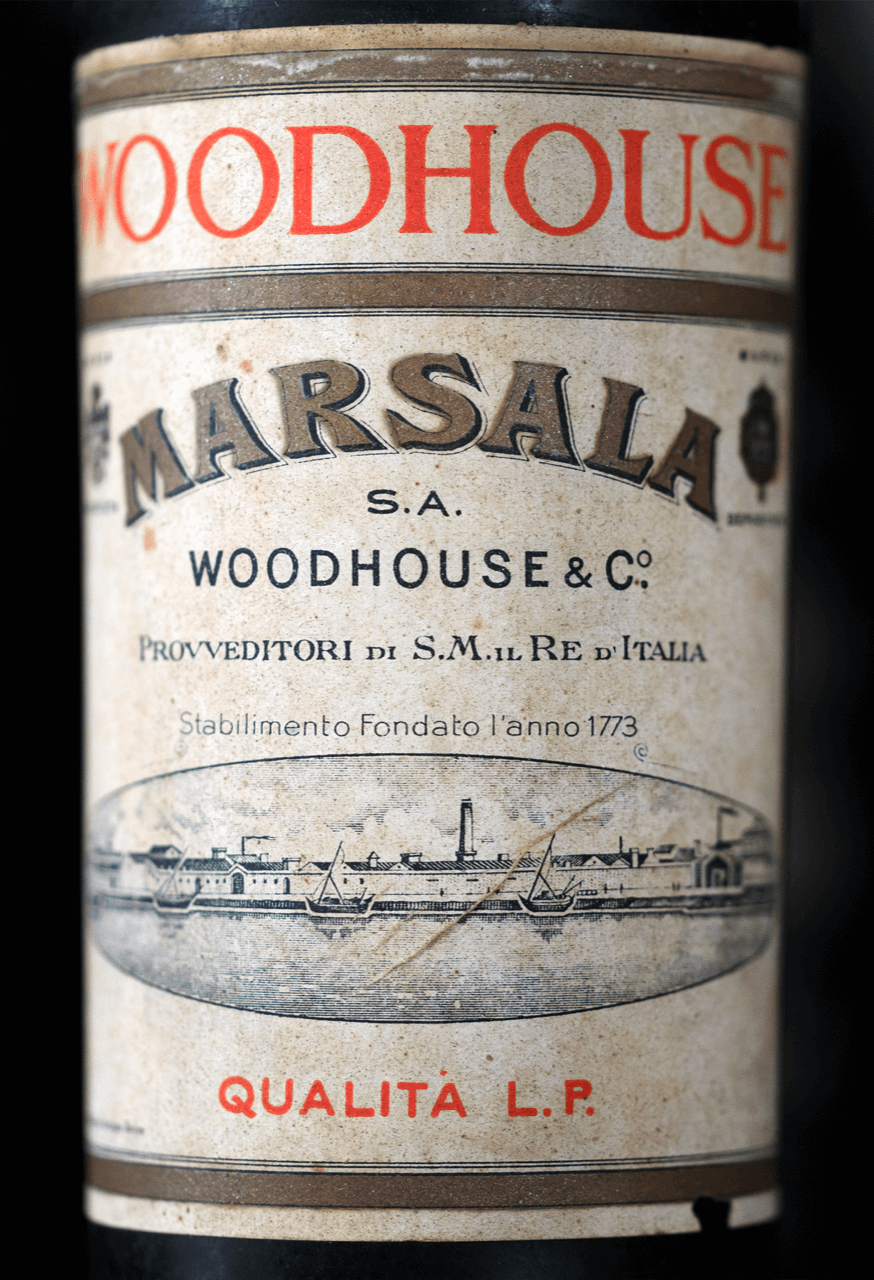

Woodhouse historical label

A Marsala Woodhouse label

The English Decade

John Woodhouse ‘invented’ Marsala, but it was the British who made it into something great.

While the first shipments were well received, with the Woodhouse family starting a business based on fortified wines, in the early 19th century an unprecedented opportunity arose for Sicilian wine to flourish. The war between France and England led Napoleon to enforce the Continental Blockade in 1806, banning British ships from docking in any French port. During the embargo, one of the few ports that remained open was Sicily, the stronghold of King Ferdinand IV of Bourbon who, in 1806, fled to Palermo to escape from Napoleonic troops. Ferdinand IV accepted protection from the British who used their influence to turn Sicily into a strategic outpost in the Mediterranean region. It was not just a military occupation, but a large-scale protectorate operation. The British presence permeated all aspects of social life in Sicily and profoundly influenced politics, culture and, in particular, the local economy, which was completely changed by the new capitalist approach.

The Continental Blockade also indirectly favoured Marsala, which was preparing to take the place of wines such as Porto, Madeira and Jerez, which would have been cut off from British trade as they were under French influence.

Dozens of English merchants arrived in Sicily from 1806 onwards, eager to expand this new market. Among them was the merchant Benjamin Ingham (1784-1861) with his nephew Whitaker, who managed to hold the record for Marsala sales in the world – at least until the mid-19th century – but who also played a prominent role in the political and cultural life of Sicily until well after the unification of Italy.

‘Ameloriating’ quality

With their rational, pragmatic and capitalist mindset, the British greatly contributed to the production of Marsala. Western Sicily, which was not yet industrialised, experienced a sudden paradigm shift. At least for the first few years, John Woodhouse simply purchased and added alcohol to Sicilian wines and stored them; the new wave of English merchants wanted to produce Marsala on a larger scale, fighting competition not only on quantity, but also and especially on quality. Initially created as an imitation of Madeira, Marsala sought to emancipate itself and acquire a more defined and unique personality.

From the early 19th century, the British entrepreneurial spirit revolutionised and perfected the entire production chain of Marsala, starting with viticulture. The Woodhouse and Ingham-Whitaker families were the first ones to worry about improving the quality of the harvests, and established direct relationships with local growers.

The proverbial donkey, now almost legendary, on which John Woodhouse junior (the son of the inventor of Marsala wine, who took his name) used to ride around Trapani in pursuit of the finest local wines, giving out advice on viticulture and winemaking. The work of Benjamin Ingham was more scientific and, most importantly, well documented. In 1830 he began giving accurate instructions to his grape suppliers on how to ‘ameliorate’ the quality of their musts.

Ingham repeatedly stressed the importance of perfectly ripened grapes and excellent base wines: in fact, in 1837 he also wrote a circular entitled ‘Brevi istruzioni per la vendemmia all’oggetto di migliorare la qualità dei vini’ (Brief instructions on harvest to improve wine quality). This document is a detailed guide containing advice on the harvest and processing of grapes, from pressing to fermentation, including the conservation of wines in so-called ‘stipe’ (large barrels).

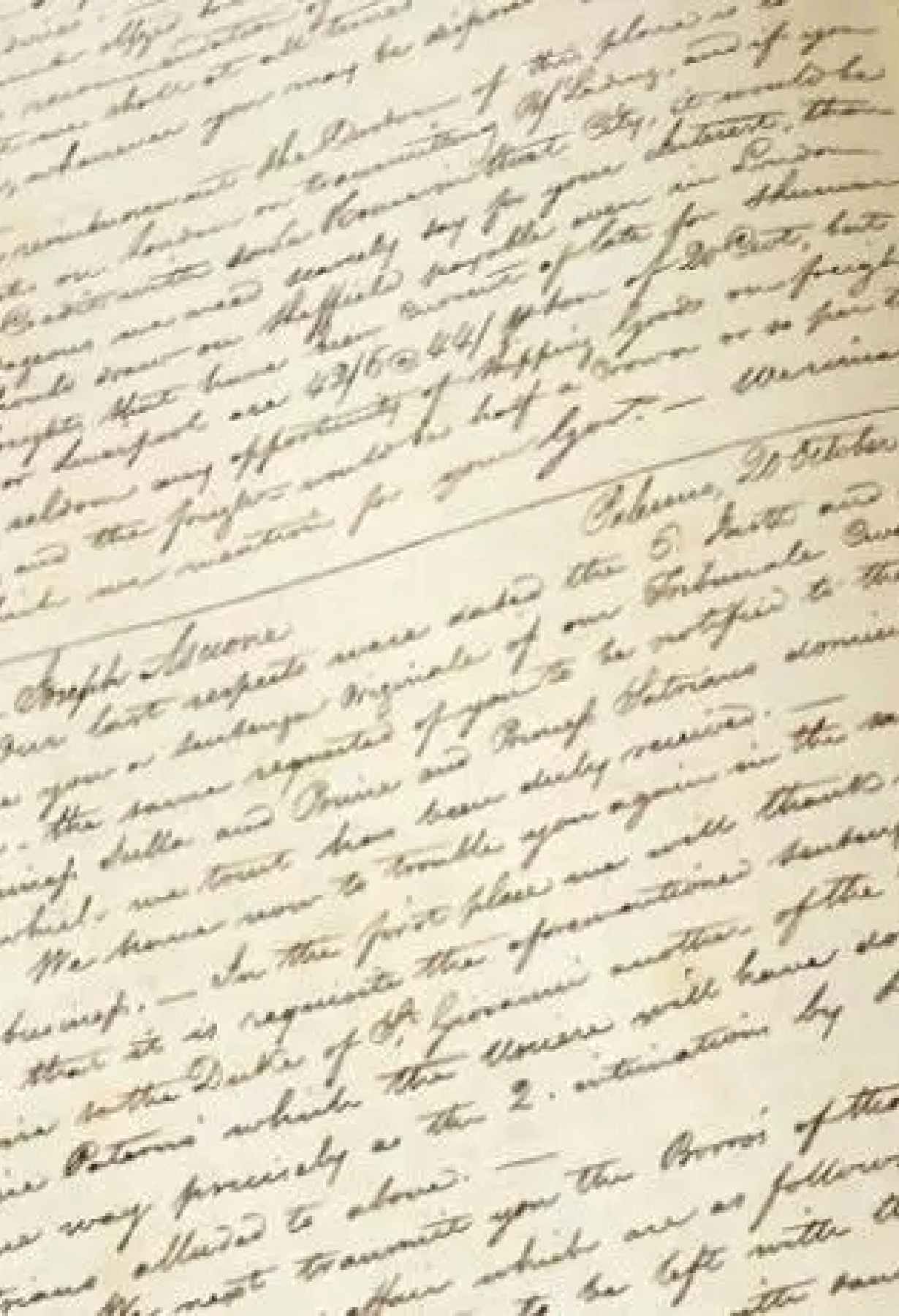

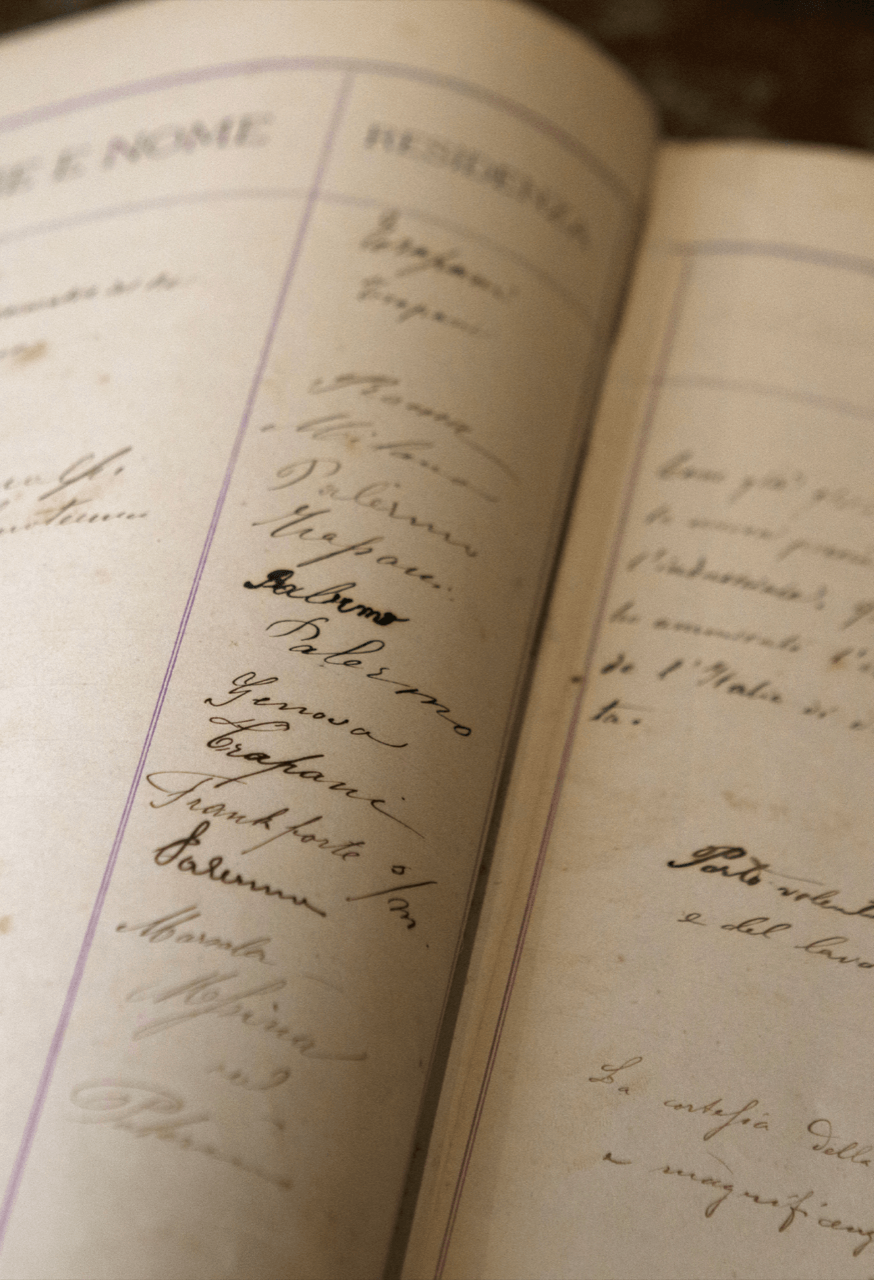

A detail from the Woodhouse registers

‘Ameloriating’ quality

With their rational, pragmatic and capitalist mindset, the British greatly contributed to the production of Marsala. Western Sicily, which was not yet industrialised, experienced a sudden paradigm shift. At least for the first few years, John Woodhouse simply purchased and added alcohol to Sicilian wines and stored them; the new wave of English merchants wanted to produce Marsala on a larger scale, fighting competition not only on quantity, but also and especially on quality. Initially created as an imitation of Madeira, Marsala sought to emancipate itself and acquire a more defined and unique personality.

From the early 19th century, the British entrepreneurial spirit revolutionised and perfected the entire production chain of Marsala, starting with viticulture. The Woodhouse and Ingham-Whitaker families were the first ones to worry about improving the quality of the harvests, and established direct relationships with local growers.

The proverbial donkey, now almost legendary, on which John Woodhouse junior (the son of the inventor of Marsala wine, who took his name) used to ride around Trapani in pursuit of the finest local wines, giving out advice on viticulture and winemaking. The work of Benjamin Ingham was more scientific and, most importantly, well documented. In 1830 he began giving accurate instructions to his grape suppliers on how to ‘ameliorate’ the quality of their musts.

Ingham repeatedly stressed the importance of perfectly ripened grapes and excellent base wines: in fact, in 1837 he also wrote a circular entitled ‘Brevi istruzioni per la vendemmia all’oggetto di migliorare la qualità dei vini’ (Brief instructions on harvest to improve wine quality). This document is a detailed guide containing advice on the harvest and processing of grapes, from pressing to fermentation, including the conservation of wines in so-called ‘stipe’ (large barrels).

A detail from the Woodhouse registers

Historical document kept in Florio Winery

‘Fine Quality’

Some of these ‘instructions’ seem basic and very obvious; in fact, they gave the impression that the winemaking region of Trapani was lagging behind and that the local farmers were reluctant to create ‘fine quality’ wines. But they also show us the passion, expertise and massive effort made by the British merchants in the Marsala area when it comes to entrepreneurship education.

The financial resources of the merchant families acted as credit institutions for setting up new businesses: loans and concessions were granted so that new vineyards could be planted, specialised workers were recruited for barrel manufacturing, and improvements were made in logistics for transporting grapes from the fields to the ‘Factory Wine’ and from there to the port of Marsala which, as a result of British investments and excise duties, became one of the leading ports in the Mediterranean region.

However, the most striking result of the invention of Marsala was that it changed the very geography of the place. While in the late 1700s there were still uncultivated fields that were largely used for sheep grazing, by 1820 vineyards extended as far as the eye could see. As for the quality of the grapes, they were carefully monitored, selected and processed by one of the liveliest, most profitable and technologically advanced wine industries in the world.

Florio and Marsala

The history of Italian Marsala wine began in 1833, when Vincenzo Florio (1799-1868) decided to purchase a plot of land situated between the Woodhouse and Ingham-Withaker factories. A goal had been set from the start: ‘to build a factory for the production of wines used like Madeira’, which was what Marsala was called at the time. Things got off to a rocky start with poor profits, especially due to well-established competition from England. But by the end of the mid-19th century, the Marsala wines produced by Florio were beginning to undermine the British monopoly. Vincenzo Florio had an ambitious industrial project from the outset, which he financed using the huge capital accumulated from trading spices, tuna fisheries, the sulphur industry, and a fast- growing merchant fleet.

So the Florio establishment was founded as a contemporary factory, provided with the best equipment available at the time, regulated by strict production rules and, most importantly, fully equipped for the ‘concia’ of Marsala, that is, the complex practice of adding cooked must to the wine followed by ageing, which was essential as it allowed it to acquire its true prestige.

While they used their fleet to break into the American, British and European markets in an increasingly successful manner, Florio’s Marsala conquered Italy, a booming market that was practically overlooked by the British. Any profits earned were reinvested in expansion and technology, so much so that, by 1880, the Florio ‘wine farm’ had grown to become a state-of-the-art oenological complex, with direct access to the sea, huge storage warehouses for storing and ageing wines, as well as a still, so that the brandy needed to produce Marsala could be distilled on site.

Historic Marsala Florio poster

The entrance to the Florio Wine Cellars

The Historic Wine Cellars

Of all the major wineries that have played a part in the history of Marsala, the Florio winery was the last to be established. However, it quickly became one of the largest, eventually outdoing its British competitors in terms of prestige and sales, and even went so far as to absorb them.

The entrance to the Florio Wine Cellars

The Historic Wine Cellars

Of all the major wineries that have played a part in the history of Marsala, the Florio winery was the last to be established. However, it quickly became one of the largest, eventually outdoing its British competitors in terms of prestige and sales, and even went so far as to absorb them.